Interview

Interview: Jonathan Twingley

In conversation with American illustrator Jonathan Twingley.

What was your journey into the arts?

I grew up in Bismarck, North Dakota. My Mom was a college librarian. My Dad was a high school art teacher. So I guess you could say that Words and Pictures were sort of our family business.

My senior year at Minnesota State University Moorhead I sent out a single graduate school application to Marshall Arisman’s Master of Fine Art Illustration program at the School of Visual Arts here in New York City. Accepted as the token Midwesterner in my class, I moved east and spent a lot of time looking back.

You mention that the blank spreads in the Isolation book are a ghost of what came before and a hint of what is to follow. I like this notion of taking time to consider the unconsidered, or to give time to something seemingly unimportant. In the media rich, fast paced society we operate in the pause seems (until recently) unknown. It is interesting that your book, Isolation, that wasn’t related to lock downs and pandemics resonates now more than ever. Can you let us know your thoughts on this?

You touch on a bunch of stuff here. Yes, the blank spreads in-between the drawings and paintings in the ISOLATION catalog collection were sort of interesting, kind of like the walls in Plato’s cave – not the things themselves, just shadows of the things, past and future. And it’s sort of astonishing how much of our lives are lived through the prism of Memory. Yesterdays are being created every second of every day, and Tomorrow is just a memory waiting to be made. Like the ghost spreads in-between paintings and drawings in a sketchbook.

I observed very early on during the growing Global Pandemic that my day-to-day routine had really changed very little: Up mid-morning, classical music out of Wyoming on Internet radio with coffee as any correspondence is tended to (now that my teaching obligations have paused, “correspondence,” such as it is, tends to be on the thinner side). I also take care of things that require a particular attention to detail in the mornings (website stuff, scanning, InDesign layouts of various projects, etc).

After working out and a late lunch I walk four or five miles, often down through Hoboken to the Hudson River with a couple of notebooks and a head full of ideas (most of this was written across the river from midtown Manhattan, the Empire State Building to my left, One World Trade down south to my right). The Art part of my day usually begins later in the afternoon, three or four hours work until suppertime and then an Evening Session which usually carries on till the early morning hours.

This routine has all been more or less maintained right straight through our current situation. What I’ve realized, though, is that this lifestyle/life of mine, which I very much love, is very much predicated on my looking out the studio window and seeing the rest of the world going on about its business. When the rest of the world is more or less keeping an artist’s hours the shine comes off a bit…

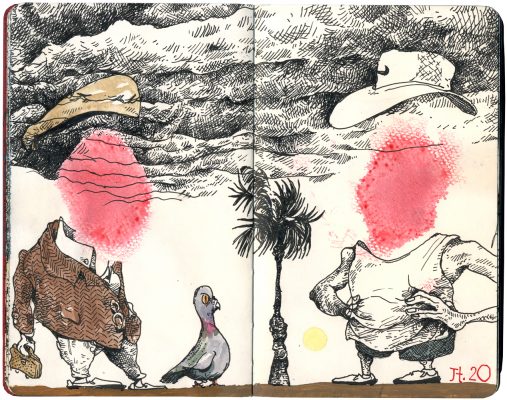

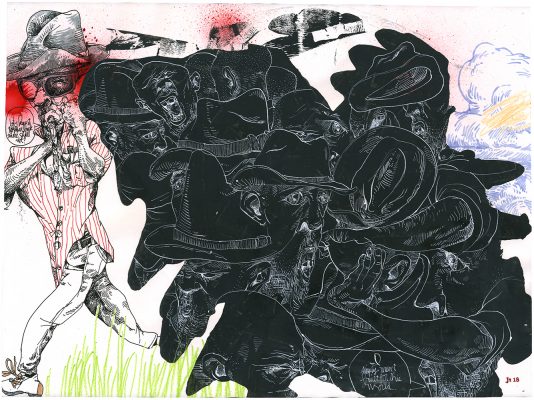

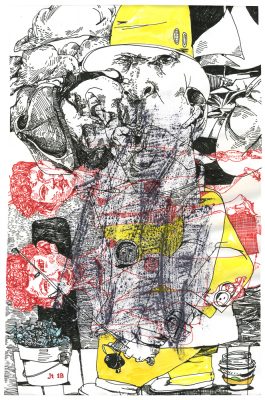

And yes, early on in all of this I came across the sketchbook from 2015 which I turned into the catalog collection called ISOLATION. In terms of Form, the book had largely been an exploration of combining pen and ink with acrylic paint using sheets of frisket. In terms of Content, on revisiting this set of drawing-paintings there seemed to be a thread running through the work – lots of lone figures, isolated, boxed in.

A psychoanalyst would have a field day with this particular collection of work, I’m sure, but for me the images took on a new relevancy. And this is how I’ve always tried to approach the commissioned illustration work I’ve done over the years. The best ‘illustration’, as far as I can tell, isn’t ‘illustration’ at all, but rather the images run on a parallel track to the written content they’ve been paired with. That’s sort of what the ISOLATION collection ended up doing: Representing a moment and a feeling that probably couldn’t have been represented as dynamically if it’d been addressed head-on.

Writing seems to play quite an active roll in your work as well as the drawing. How do the two compliment one and other?

Writing and drawing have always been of a piece for me, complimenting one another depending on my mood or the subject or the project. And this might go back to my upbringing – one year when I was six or seven years old my Mom bought me this special sort of colouring book which was completely blank, except each spread had ruled lines on the left-hand side and a vertical rectangular box on the right, encouraging the child in possession of this fancy book to write and illustrate their own stuff. The paper stock wasn’t cheapish, like in most coloring books. This was a more serious task, the paper stock seemed to suggest. Did my Mom recognize something in this precocious little person that that little person had yet to realize in himself (the whole Nurture vs Nature game can be a fun one to play, can’t it?)? Truth is, I never touched the fancy blank coloring book. Something about the rigid “WRITE HERE” and “DRAW HERE” format turned off the spigot of my little creative mind.

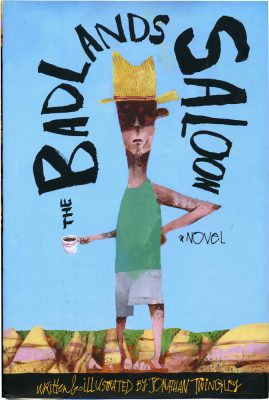

All these years later, when rummaging through shelves of cheap, hardcover sketchbooks, trying to find something I’d remembered putting down in one of them, the pages are covered in nearly equal parts with both words and pictures. As an example, in 2009 Scribner published a novel I wrote and illustrated called THE BADLANDS SALOON. There are a couple of sketchbooks from 2007 and ‘08 more or less devoted to telling this story. The books alternate between hand-written chapters, start-to-finish (which I’d then later type up on my iMac and edit/revise/re-write/etc), and double-page spread ink drawings which were eventually translated into the acrylic paintings on unstretched canvas that ended up in the book. But everything started with a cheap blank book on my lap and a fountain pen loaded with permanent black ink.

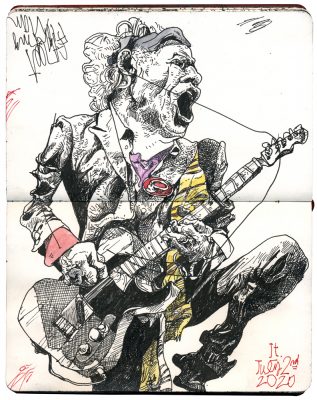

Since I was 12 or 13 years old, hoping to emulate Mort Drucker or Don Martin or Charles M. Schultz’s beautifully human shaky line in his later work, I’ve been drawing with ink on paper, dip pen and wet ink or free-flowing fountain pens. But unlike these early inspirations I’ve almost never laid out any sort of pencil under-drawings before I begin. There are exceptions here, of course, usually necessitated by commercial realities, but I’ve come to trust – and ask those commercial interests when they call to trust along with me – that if we begin with a general idea, the thing will turn out best – and most alive as a drawing and an idea – if I/we just follow the line along to its conclusion.

And drawing with a fountain pen is very much like writing. In his spectacular book THE CREATORS: A HISTORY OF HEROES OF THE IMAGINATION, Daniel Boorstin describes how the ancient Egyptian craftsmen who carved hieroglyphs into stone were referred to as ‘figure writers’. Isn’t that wonderful? Eastern cultures too have historically not really recognised any sort of demarcation between drawing and writing and very often present the two as one, whether on a Chinese scroll telling a story in pictures and words, or a Japanese haiku where the calligraphy itself is a pictorial statement. Writing and drawing are both trying to get at the same thing though in different ways. When combined, they’re like storytelling in stereo.

People are often curious as to what my workspace looks like. I suppose the first was a corner of my Dad’s basement studio on South Sixteenth Street in Bismarck. His studio was always in our home and I guess I’ve intuitively sort of followed suit, dedicating a room wherever I’ve happened to be living to this thing that I do. But the “studio” itself – the physical location – is sort of irrelevant. In the end it’s simply a room with a table and an easel and a chair and me, every day, figure writing.

I’m interested in the idea you mentioned that sketches and drawings come into this world and lie dormant until they decide to assert themselves. This implies, in part, that they have an existence beyond you as the creator. Can you elaborate on this?

Asking the question “Where do drawings come from?” can get real metaphysical real quick. I certainly don’t believe that drawings or novels or songs or anything else pre-exist in some sort of elusive plane, just waiting patiently for us to give them form. I do, though, often approach the work I’ve made as something almost outside of myself, something I’ve simply found rather than created. It’s not so much “Look how awesome a drawer I am!” but rather “Look at this interesting thing I found.” I’ve spent years teaching at the university level here and there and the bit of advice I’m always compelled to offer students is: “Don’t think.” Now, the last thing I’d want is for a student to run home and tell their father or mother that a professor at their very expensive college or university told them not to think.

As a suggestion, what I mean is to pour everything you can get your hands on into your brain – news of all perspectives, the great literature of the world, music, history, scientific journals, atlases, biographies of the great creative minds you admire, the font choices on the signs above storefronts and what people are wearing as they walk past those stores below those storefront signs, absolutely EVERYTHING – and then just begin. Whether it’s writing or thumbnail sketches for a conceptual installation you’d had a hint of an idea about but just weren’t sure. The editor in our brain is necessary but he often gets in the way, especially at the beginning of something, when your idea is at best only a hunch.

Somewhere along the way I made a note to myself (probably inside the back cover of a sketchbook I was keeping at the time): “Move the pen. It knows what to do.” That’s where drawings come from.

Do you like this artist?

If so, why not write a comment or share it to your social media. Thanks in advance if you can help in this way.