Journal

Interview: John Vernon Lord

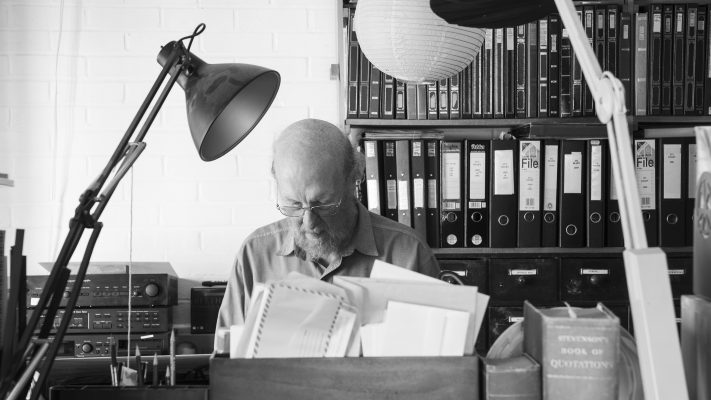

Interview with illustrator John Vernon Lord.

Introduction by John Vernon Lord

In July 2021 I received an email message from Gavin Ambrose suggesting he would like to publish a book of my drawings and sketches for his Unseen Sketchbooks series of books. At the time he had recently seen an exhibition of my notebook drawings and illustrations at the Ditchling Museum of Art and Craft.

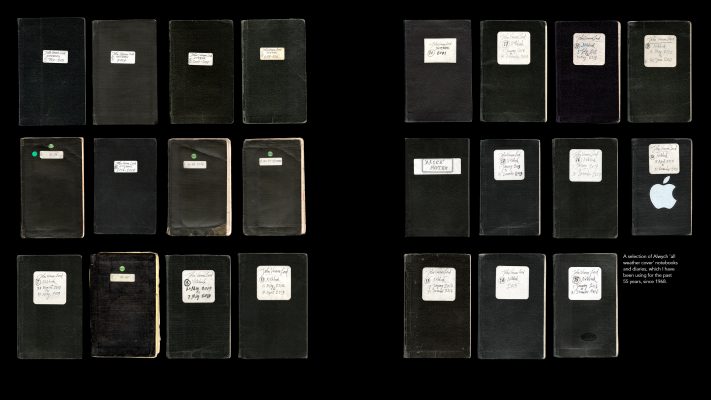

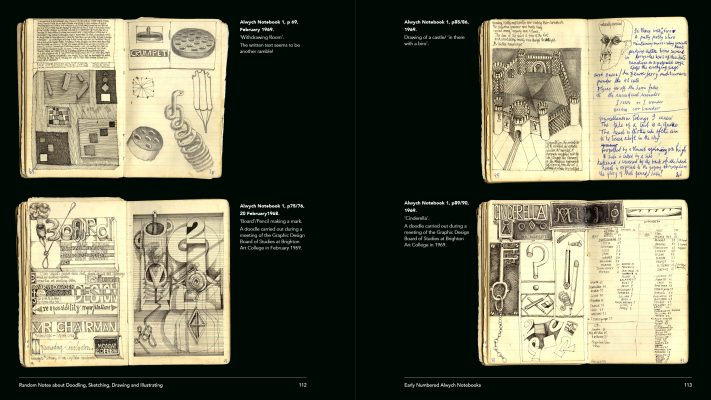

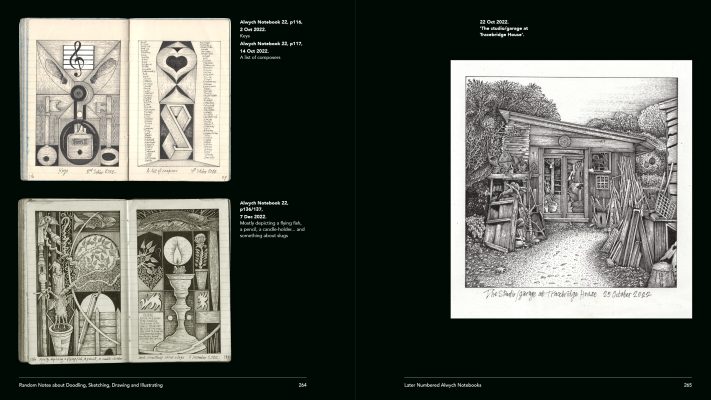

In October 2021 I started planning the selection of drawings that might be included in the book. During the course of time the number of drawings was increased as I continued to produce more drawings in my notebooks. The earliest drawings were sketches I had carried out when I was a first year student at Salford Art College in 1957. The last drawing was a studio/garage drawn in October 2022. Thus, the book includes drawings carried out over a period of 65 years from 1957 to 2022; aged from 17 to 83.

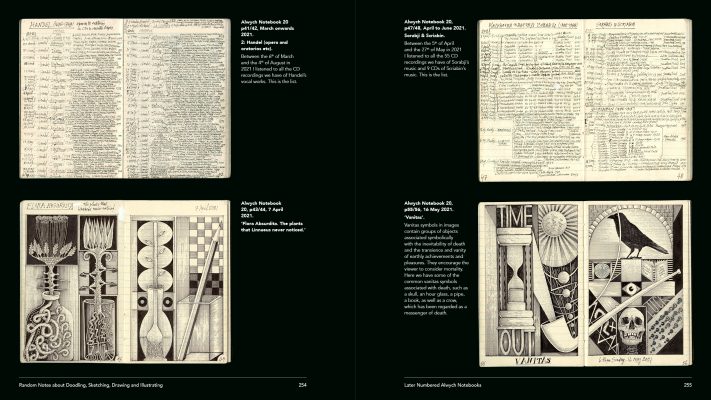

The title of the book is Random Notes about Doodling, Sketching, Drawing and Illustrating. Gavin was keen for me to write 4 essays about Sketching, Drawing, Doodling and illustrating as well as something about my diaries and notebooks and to ‘punctuate’ the individual captions ‘with conversations’. My friend, the author and broadcaster, Brian Sibley wrote the introduction. All in all the text includes about 37,000 words among the 290 pages of the book itself. There are about 700 pages of drawings and notes from, sketchbooks and notebooks etc.

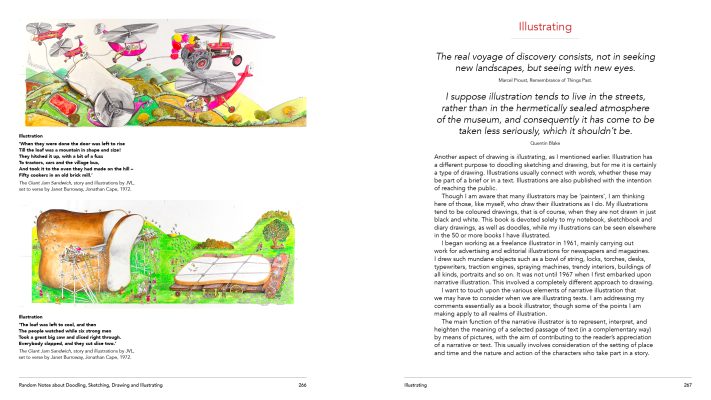

The book also includes a small selection of book illustrations that cover 45 years of activity. These include: The Giant Jam Sandwich, published in 1972; Conrad Aiken’s Who’s Zoo 1977; The Nonsense Verse of Edward Lear 1984, Aesop’s Fables 1989; Icelandic Sagas 2002; Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland 2009 and Through the Looking Glass 2011; James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake 2014 and Ulysses 2017.

The first scanning session began at the Museum on the 16th of November 2021 and all subsequent 12 scanning sessions took place, mostly in my studio at home. The final scanning took place in January 2023.

Gavin Ambrose: Part of your practice as an illustrator is contained in notebooks and diaries. They are sequential, you start a book and then add page by page until it is complete. The pages are often filled to the outer borders of the page and are very intricate in nature. How does this format and daily structure inform your practice?

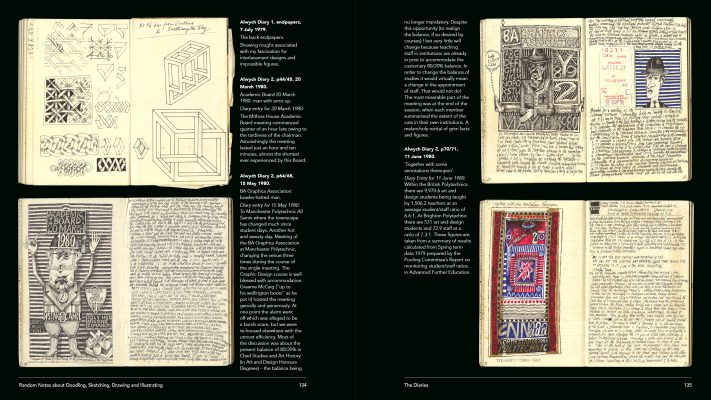

John Vernon Lord: Your query about my tendency to fill to the outer borders of a page very intricately is probably caused by my grandmother, who brought me up when I was a child. When I was drawing as a young child, she used to complain if I left any blank spaces on the paper. She used to say “John, there is a world war going on and you can’t waste scarce paper like that – fill the sky with such things as clouds, rain, insects, birds, aeroplanes, the sun, the moon, the stars, a rainbow and even lightning if you want”.

I have always been interested in the dynamics of the three main formats for making images – the square; – the horizontal (often called ‘landscape’) – and vertical (or ‘portrait’) formats. They all have intriguing compositional constraints, considerations and dynamics. I think square formats present a greater challenge than the others. It seems to me that horizontal (or ‘landscape’) formats offer more possibilities in creating dynamic qualities in an image.

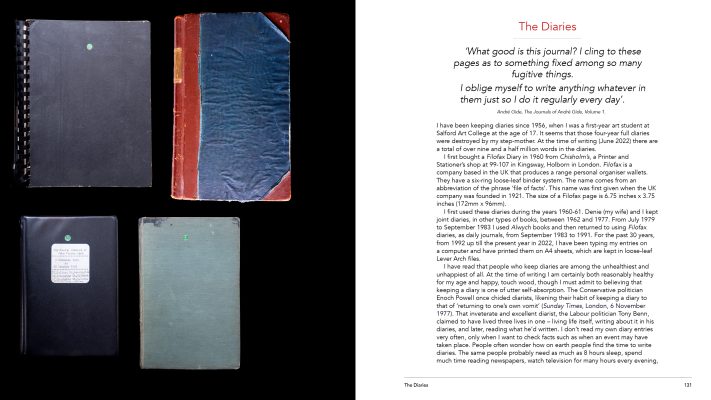

GA: The process of diary entries is time consuming but is often said to be liberating. You write an entry or draw an image, contemplate on it, and later relive it. Can you talk about the process of doing these entries, who are they for and what conceptual boundaries do they afford you?

JVL: People often wonder how on earth people find the time to write diaries. The same people probably need as much as 8 hours sleep, spend much time reading newspapers or are preoccupied with social media on their mobile phones, watch television for many hours every evening, and have many of their own priorities that are equally as fatuous and time-consuming as the diarist.

I don’t really have anybody in mind when I write a diary’ I have to be free when I write entries. An audience would stifle what I want to write about. My diaries mainly chronicle daily events, however prosaic and inconsequential they may be. They help me understand the day just lived, by reflecting upon it, and prompt me to come to terms with what needs to be done. They are a useful aide-memoir. What is my motive for writing a diary then? It is a tidying up process I think. It helps me take stock of things – to recall happenings and try to make sense of them. There is this futile impulse within me that somehow wants to grasp at all these yesterdays – a desperate urge to record things, however trivial. The impulse to write about uneventful days is no less important than those that may be more exciting. I have no concept of boredom. On the rare occasions I actually get down to reading these old diaries I am almost always disappointed with the result. It is as if I had tried to catch a bird but had only snatched hold of a few feathers.

A sketchbook is a kind of visual diary and a reference book. In a diary you are entitled to write whatever you want to for there is usually no intended reader. It is the same with a sketchbook. There is no pressure to produce perfect drawings in a sketchbook. You can experiment and develop ideas and discover new ways of drawing on the way. Sketching is an opportunity to make mistakes without feeling that you are a failure.

GA: What are the boundaries borders of illustration? Are you ‘contained’ in any way by illustration, or can you travel in and out of that space? Is the sketchbook part of this process?

JVL: We use just twelve pitches in Western music. The combinations of these twelve pitches is vast and practically endless. The combination of all kinds of instruments and voices offer a vast variety of music. Similarly the variations of images created by illustrators are also endless. Think of the variety of illustrations created by William Blake, Quentin Blake, Frances Barlow, Milton Glaser, Thomas Bewick, Emma Chichester Clark, Edward Gorey, Susan Einzig, Gustav Doré, Stanley Badmin, J.J. Grandville, Kathleen Hale, Maxfield Parrish, Sara Fanelli, Raymond Briggs, Alan Baker, Arthur Rackham, Shaun Tan, Ralph Steadman, Mini Grey, Gennady Spirin, Kate Greenaway, Alan Sorrell, Norman Rockwell, Jane Hissey, Wenceslaus Hollar, Saul Steinberg, Beatrix Potter, Posy Simmonds, Maurice Sendak, Fougasse, and Shirley Hughes.

Pictures (and I include photographs here) distinguish themselves from the other arts in that they do not move in time as do music, dance, theatre, film and reading. Drawings and illustrations are flat, still and silent and they are confined within boundaries at the four edges. This is their limitation but it is also their special virtue. All drawings are abstract and everything in them is a symbol of something; symbols of objects, symbols of shapes and space, and even symbols of themselves. A distinguishing feature of the pictorial arts has been nicely put by Matisse, when he said, “Whereas the writer has to use the shared language of speech every artist uses his own self-invented visual language”.

GA: I’m interested in what we mean by creativity. How do you explain or think about it? We have both taught in creative courses and it is interesting seeing people arrive as students and leave having crossed over to being early practitioners. Often these students are from different cultural backgrounds and countries transforming through the university system. How has this affected your thinking about creativity in your teaching practice.

JVL: For me ‘creativity’ is the ability to come up with original ideas and to attempt to produce unique images unlike anybody else. This may involve solving visual problems in a unique way that communicate. These may come from inventing a new visual language or by creating an original graphic use of materials.

Illustrations may take on the form of the visual clarification or explanation of something that cannot be expressed in words or seen in the normal way. Visual ideas may complement words and interpret texts. Illustrations may show what the world is like in the present, what it used to be like in the past, and what it could, should or might be like in the future. Illustrations can explain by means of diagrams or express concepts that cannot be seen in the normal way. They may inform, persuade and warn of danger. Pictures can alert people’s consciousness or conscience. They can also celebrate the beauty, or emphasise the ugliness, of something. They can amuse, delight and move people and they can show impossible situations and a world that doesn’t or cannot exist.

One of the main challenges of teaching for me was aiming to help students create unique images that communicated. This involved encouraging them to discover their own uniqueness, both in seeking to create original concepts as well as looking at fresh ways of drawing and composing images. Convincing students that working hard was the only way to achieve this. As for teaching students from different cultural backgrounds I always thought it best to begin by believing that all students were beginning on the same level playing field. Celebrating cultural diversity and understanding the differences in people is crucial.

Footnote by Gavin Ambrose

Making a book is always a complicated process. When I established Unseen it was with two aims. Firstly, to look at design and creative process, and not just to focus on finished product, and secondly, to produce books without the usual constraints a publisher would usually apply. This book started as a look at John’s intricate and detailed sketchbooks, but it soon became clear John, like many illustrators, has a huge catalogue of unseen material.

We spent many hours talking while scanning, which became part of the process of the book. Talking about the pages of the sketchbooks and notebooks started to reveal what the pages contained. Part diary, part imagination and speculation the pages are a history of John’s career as an illustrator, his position as an academic and his life with his family and friends. This tries to oversimplify the works by compartmentalising them into career, position, and life. In reality, John’s career, position and life are all one great big mix that inform and enhance his work. The commitment John has to drawing wouldn’t be abated if he hadn’t done this as a career. Hundreds if not thousands of these intricate drawings and notations have been made without a primary reason of ‘showing someone’. The drawings are created as an act. An act of observation, thought, remembrance and contemplation. They aren’t made for a purpose – they are the purpose.

We started this book not really knowing how many illustrations it would contain or many pages it would run to. It ended up running to nearly 300 pages with more than 700 illustrations. My only disappointment is that it didn’t run to 3,000 pages and over 70,000 illustrations, which with John’s body of work would be possible.

This book has evolved into a rich history of John’s works and thoughts and has many parallels to my own life. We both worked for the same University, at Brighton, have similar family stories and many intersections of life that cross over. John’s wife was a nurse for many years at the Evelina hospital in London, where my daughter goes for her surgery. During this process I’ve realised you really need time to truly understand someone’s work, and even now I feel I’m only scratching the surface of John’s output as an illustrator.

Buy BookThe works of Helen Kitson are physical ‘collages’ or collections of ephemera and found items.

Do you like this artist?

If so, why not write a comment or share it to your social media. Thanks in advance if you can help in this way.