Interview

Interview: Robert Lundin

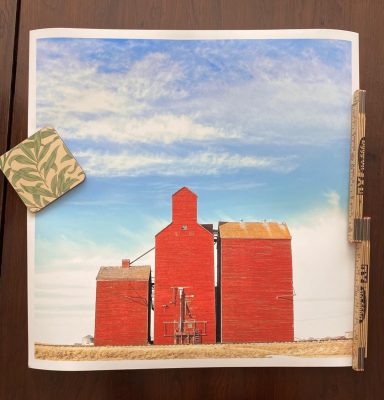

In conversation with Stockholm based photographer Robert Lundin. Robert originally studied business economics in Rotterdam and quit his job around five years ago to concentrate on his photography.

Robert is self-taught and attends courses at the Fotografiska Academy in Stockholm. We were first shown Robert’s stark, haunting images by @gailsargerson, thanks Gail.

Can you talk about your journey into or interest the arts?

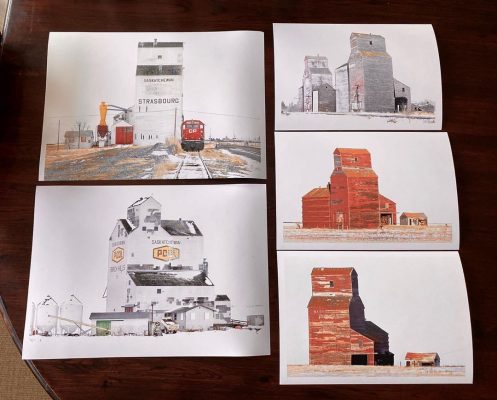

I had an unexplainable interest in technical drawings from the times my dad developed factories and I myself built large, wooden radio control aircraft from technical drawings. Subsequently I started shooting straight projections of old buildings and factories. I started in B&W and had a dark room at my parents.

It was during the early ’80s when I started finding my true passion for photography. My studies in business economy were a chore. The revelation of art photography was then an overwhelming discovery, opening a whole new world of what motivation and passion actually should be like.

One special experience was when I – on a long leg stretch through Rotterdam procrastinating my studies once again – happened to see the Goethe Institute where an exhibition of the German filmmaker Wim Wenders was open to the public. His pictures blew me off my socks through their matter-of-factedness in depicting mundane towns in rural USA. He framed structures, lines, colours in an almost abstract way, finding visual balance and beauty in the banal and every day. That one can take pictures like that to tell a story? Unimaginable!

There are of course others I have enjoyed and been inspired by since then, most from the so-called style of New Topographics, all telling stories of everyday life and settings with a very investigative eye for the beauty in the casual and unintentional. Other early influences are Joel Meyerowitz, Edward Hopper and the great Wright Morris. The Bechers not so much though – perhaps surprisingly – but for their fascination for typologies.

Your work focusses on industrial buildings, that are both imposing and foreboding whilst being peaceful and beautiful. What is it about these you are interested in and what are you saying by photographing them?

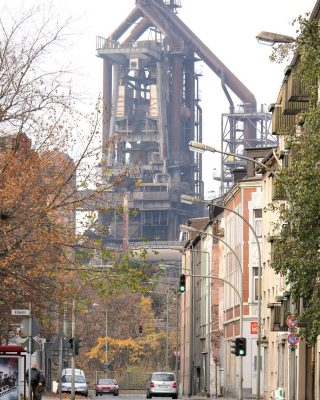

A feeling of impressiveness. I describe it – a bit pompous – the sublimity of man in this big machine we call society.

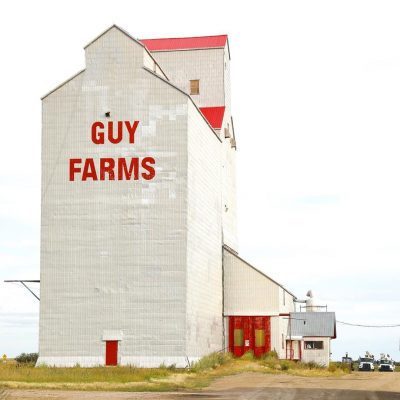

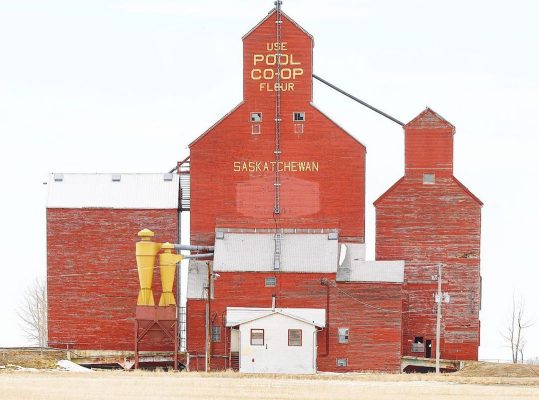

I have not only photographed grain elevators in Canada, but also the old steel industries in Germany and Belgium. What attracts me is the feeling of awe when experiencing the contrast between the vulnerable man while strenuously having constructed this complex and sometimes daunting environment, full of gigantic, monstrous mechanisms.

There is also a certain time factor, without which I think many of my subjects wouldn’t make the same impact. Old buildings in general that have survived human generations become beacons over time and people gone by, they make us remember and reflect our own mortality and the surprising changeability of what we think are stable constructs.

Whereas people are undeniably central in the story – their imprints are absolutely everywhere in my pictures – but they are not the main subject photographically.

Can you talk about your process of working? How do you work, how often, is there a particular pattern?

I always have an idea of the impressions I want to achieve, most often based on what I said above: Contrasts and visually well-balanced compositions.

Practically speaking, for my industrial photo projects in Ruhr, Charleroi and Canada I have had a high energy approach staying in the ‘flow’ doing long days and using a small car to be able to cover as many photo spots and angles as possible in a day. Evenings doing editing and quality checks. In Canada I drove 400-500km and visited on average nine towns or areas with grain elevators per day, approx 14 hours of ‘production’ per day. I often shoot while sitting in the car and quickly drive around and find new angles.

Technically I often use 50-300mm as to compress the picture and most importantly: to get rid of crashing lines in the vertical plane. One interesting discovery while shooting from the car this winter in Canada was that the hot air streaming out through the open window distorted the image considerably. Only one solution: getting out of the car and face the chill.

Do you like this artist?

If so, why not write a comment or share it to your social media. Thanks in advance if you can help in this way.