Interview

Interview: David Shillinglaw

In conversation with artist David Shillinglaw. Born in Saudi Arabia, David was raised in London, and now lives and works in Margate.

Can you talk about your journey into or interest in the arts?

It was always there as far back as I can remember. At school, art always felt like a treat or a chance to play. I went to college and university, loving every class from photography to ceramics, but I always gravitated towards drawing, painting and collage. I had many jobs after graduating, but always had a studio space and kept making work and aiming toward group and solo shows. My first exhibition was in a bakery in London’s Covent Garden. After many years my determination and dedication paid off and I found myself doing it full time. Now my job / practice is a balancing act, juggling paid commissions and murals for clients, doing work for charities or for the fun of it, and then being in my studio making work for myself or an exhibition. Each part of my practice feeds the next: the studio work feeds and feeds off the commissioned work. I try to keep everything flowing together, stylistically and conceptually; for me its all the same practice.

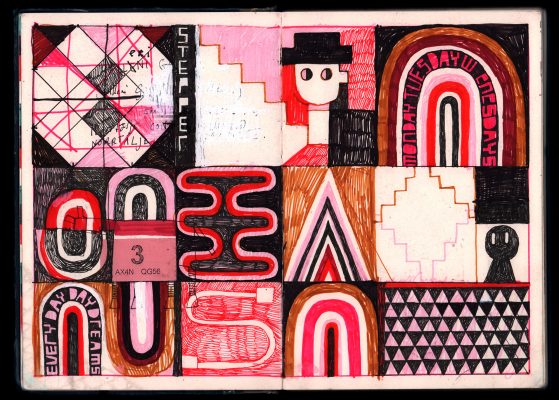

Do you use a sketchbook? I’m interested in what a sketchbook means to you and your work, or how people develop their ideas.

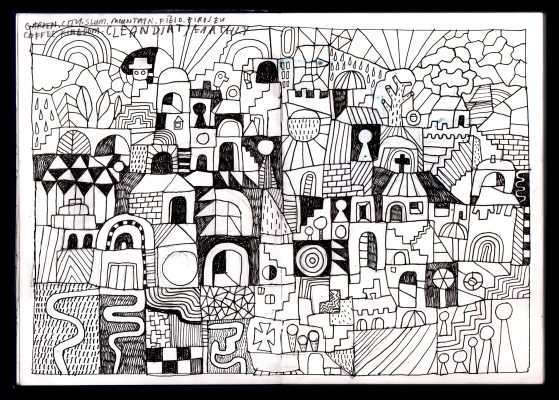

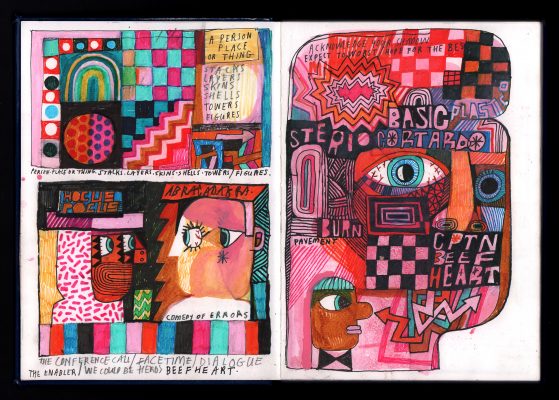

Everything starts in a sketchbook, I feel that some of the best things I produce happen in a sketchbook. It is a sacred space, it is a personal space, like a journal or diary. I figure things out in sketchbooks, I plan things, I fail and learn things. I carry a sketchbook with me all the time, and usually have several on the go at any time, different sizes, different paper, different sketchbooks for different trips. Some are more for drawing and writing, some are more for collage and painting.

Your work uses both illustration and typography; can you talk about those two processes?

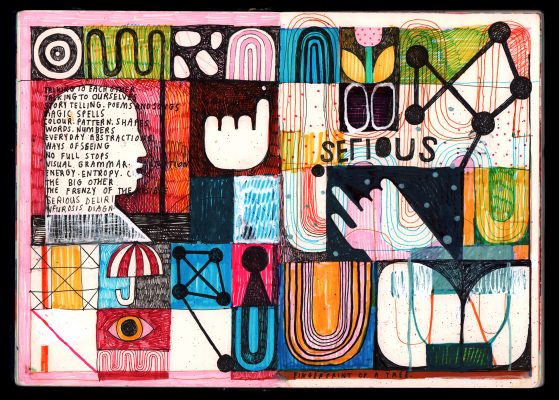

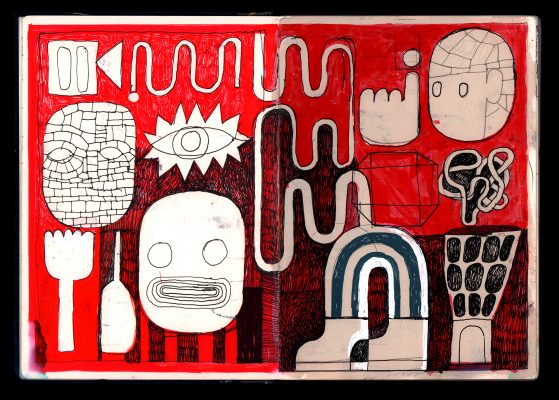

I try to not separate elements, I just collect images and marks. I am constantly searching for harmonious ways to balance the visual space. Sometimes the elements in an image are symbolic, like a key or a hand; at other times it’s pure abstraction, it’s just about what the space calls for. I love typography and numbers; they hold a lot of power and meaning, but ultimately they are all abstract until you learn their meaning. I have a fascination with semiotics, and how we use signs to communicate. I used to include a lot more text in my work — I was really into list-making and word association, idioms and jokes — but I started to feel the work was too reliant on people’s understanding of the written language, and wanted my work to be read by people of all languages, and children. I am trying to speak in a universal language about universal themes. The past year I have been drawing a lot of plants and trees; I feel like these are immediately recognisable to everyone, and even though they are very basic they can also be symbolic and carry a lot of meaning.

You often use pattern and form. What themes are you exploring through your work?

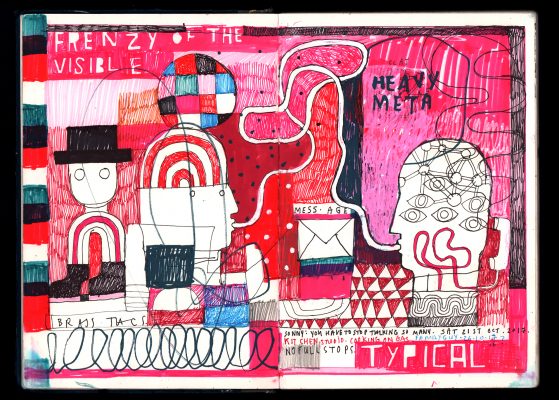

The golden thread I always hold onto to guide me into and out of the work is the human experience. Without dictating a specific meaning I want people to recognise themselves and planet Earth in the work. I borrow from micro and macro systems and structures and bend things into my own vocabulary. I think of paintings as songs or poems: they are to be played; I want you to enjoy dancing around them with your eyes and your brain. There is a deliberate sense of chaos, which aims to mimic the kind of chaos you experience when walking down a street or through a forest, or having a conversation at a party, or the layers of thoughts that stack up in your own mind. All of my paintings are a failed attempt to organise this energy and fix things in place. I am rarely still and the world around me is moving at a fast pace, [and] this fuels my work, both aesthetically and conceptually. I think in layers rather than a finished picture. If you want a picture of something, just take a photo; a painting, and in particular a collage, can do things a photograph cannot.

Can you talk about your process of working. How do you work, how often, and is there a particular pattern?

I would say I work every day, but that changes depending on what the work is; sometimes I feel I am working when in my sketchbook at the kitchen table, other times it’s more obvious because I am up a cherry-picker painting the side of a building.

The mental and physical don’t always align. Sometimes the hardest work is the thinking. The act of painting is often playful and I lose myself in the action of it. I love going to the studio: it is a very important part of my practice, I figure things out in the studio in a way I can’t anywhere else; I make mistakes and discover new things, a lot like being in a kitchen trying out new recipes.

In the studio I work on many things at the same time. I consider this cross-pollinating: ideas, colours, materials bleed from one piece to another. Some pieces I work on for several years, adding and taking away until the work is complete.

Often an exhibition will dictate a time frame and I will build up to a date and a specific space in mind. The works borrow and steal from each other, colour schemes emerge, and conceptually the body of work becomes one thing. Sometimes I’ll make something just days before the show that completely makes sense, but it has happened as a result of all the other works, in the way a musician will write a bunch of songs and maybe the chords and lyrics and harmonies give birth to a new song.

I honestly don’t plan too much; I need to discover things in order for it to feel authentic; too much planning can feel like I’m designing pieces that have an end result in mind. I want to be taken by surprise and feel genuinely excited about the work to the very end.

Do you find the process of creating work relaxing or therapeutic? I’ve become increasingly interested in the relationship of the sketchbook and the work to the artist.

I would say yes and no; I need to make art as a way to process things that are going on. For me it is definitely therapeutic and a necessary mediation, but there is a struggle there too. I find both agony and ecstasy in the creative process: I think about it all the time, I build up to it, almost like preparing for a fight. I have a child, so time is very precious; I used to just come to the studio for a whole day or very late at night, [but] now all my time revolves around another human.

Time is the currency. I have to save time, make time and try not to waste time. As a result my expectations are heightened, the whole process is heightened; this can lead to being very productive and feeling very happy with what I have made, or the opposite. I think it’s important to remember that you have to put the work in to get results, and it is important to fail. I often think of this quote from Samuel Beckett: ‘Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.’ To answer the question, it can be relaxing, but I think I learn more when it’s not.

Do you like this artist?

If so, why not write a comment or share it to your social media. Thanks in advance if you can help in this way.